While at the IUSSI conference in Australia this summer, I got the chance to tour some stingless beehives. It was a really lovely experience, and the thing I was most struck by was how small these little bees are! When we approached the hives, the air was busy with an active cloud of small, black insects that looked more like small houseflies than the bees I was expecting. These stingless bees, sometimes called “sugarbag bees” or meliponines, are cousins to the familiar European honeybee. Both species belong to the family Apidae and the subfamily Apinae, but the sugarbag bees are members of the tribe Meliponini, whereas honeybees are in Apini.

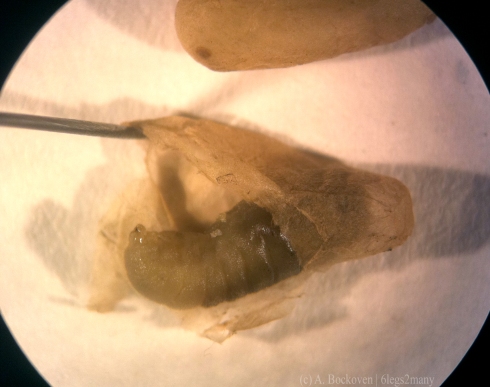

Inside the hive of Tetragonula carbonaria, a stingless bee. The brood mass is visible in the center, the honey-storing resin pots to the left, and the yellow pollen baskets to the right.

Sugarbag bees are native to Australia, and generally dwell in small cavities, such as hollow logs, rock crevices, or even underground. As such, many species can be kept rather easily by humans, in small hive boxes not much bigger than a shoebox. The bees have reduced stingers, which are incapable of stinging. Although they can bite, with their mandibles, they are fairly unaggressive. The beekeepers opened several hives for us and allowed us to look at the comb structure, and the swarming bees seemed utterly uninterested in their human invaders. The comb of these bees is particularly interesting, as eggs are provisioned in closed pods rather than larvae being fed and cared for by workers as is the case in honeybees. The pattern by which the bees advance the “brood mass”, or comb, varies from species to species, from the spiral seen above to more organic, serpentine patterns. (I have pictures. I have so many pictures. A topic for another post.)

A newly eclosed stingless bee worker, with sisters visible still in their cells. (Tetragonula carbonaria)

The sugarbag bees make a honey that is lower viscosity and more liquid than that of European honeybees. It’s quite delicious, and varies a lot between species and depending on what the bees have been feeding on. The bees make The beekeepers told us that stingless bees are apparently becoming a popular “pet” in Australia, with most people keeping them more out of interest than for their honey. In fact, our tour guides had recently made the switch to primarily rearing hives for sale, and such hives sell at about $400AUD.

Recent Comments