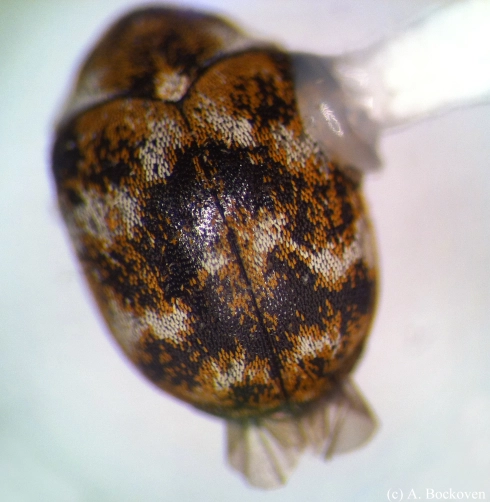

Here’s a cool beetle I found a while back, all the way down in Argentina. This is a member of the family Elateridae, the click beetles, so named for their snapping/jumping defense mechanism. Click beetles are cool enough that I really ought to give them their own post, but for now I’ll just direct you to Ted McRae’s recent excellent post on the subject. There are tons of species of click beetles, all pretty easily identifiable by their elongate shape, back pointed pronotum, and the mesosternal spine they use to go click.

This particular click beetle has an extra trick up its sleeve.

The glowing click beetles are a genus (recently revised into several genera) notable for the two glow-in-the-dark spots on their pronotum. Several species are native to the Southern US. In researching these beetles I find a mixed bag of explanations for why they glow. The adult beetles bioluminesce at night, and this light, which can vary in color from species to species, is involved in species-specific recognition cues in mating, much like fireflies (Feder & Valez 2009).

The eyespots also brighten when the beetles are startled, suggesting a warning, anti-predator function. Facultative aposematism (warning colorations that are only sometimes used) can be especially useful when an organism has different categories of predators, some of which will find it distasteful and learn to respond to warning coloration and some of which will not (Sivinski 1981).

Finally, both the larvae and the adult beetles bioluminesce and the light may also function as an attractant for small insect prey, particularly for the larvae. (My source for this last bit is Wikipedia. Make of that what you will.)

Recent Comments