Bee fly with eyes eaten out by dermestids.

Here’s a sight no insect collector wants to encounter in the collection boxes. I was sorting a mixed box of pinned specimens when I found that this fuzzy bee-mimicking fly had met a second untimely fate (the first being the fate that led him to be pinned in my collection). As you can see, the large bulbous eyes that occupy most of the bee fly’s head are, um, no longer occupying. In fact, they’ve been rather neatly eaten away. Apparently, bee fly eyes are delicious.

Dermestid damage in an insect collection.

With mounting horror I sifted through the collection box and found all the signs: tattered insects, scattered frass, and (the smoking gun) cast off larval skins. One hairy skin stuck to the wing of a tiger moth whose hollowed out abdomen had apparently made a tasty treat.

Cast off exoskeleton of a carpet beetle larva (Dermestidae).

Dermestids. Oh, joy. Is there any insect that is more unwelcome in an insect collection? (Actually, my friend Paul had an unpleasant experience with a voracious colony of fire ants, but that’s another story.) These guys, often called carpet beetles or hide beetles, are dietary specialists on dry, high-protein organic materials. Everything from dandruff to leather to natural fiber carpeting may become their food source.

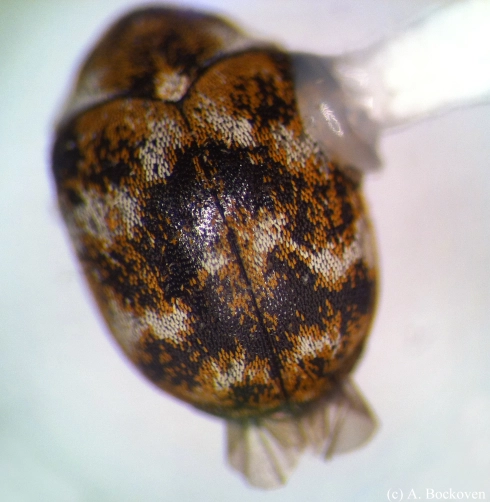

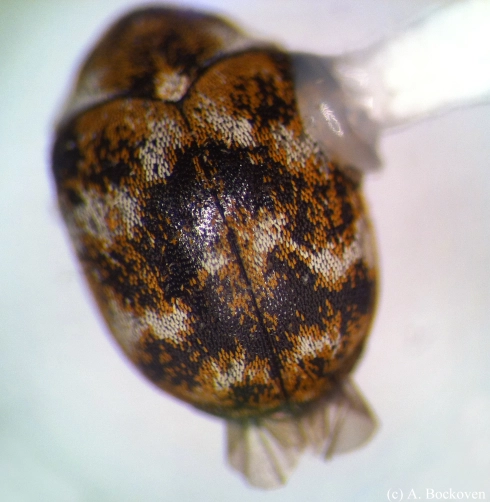

Carpet beetle close up (80 times magnification).

This not only makes these beetles a damaging household pest, it makes them both dangerous and very useful to to people who work with dead things. When they’re not uninvited guests, dermestid beetles are frequently used to “clean” skeletons, removing hide, flesh, and all. If you’ve every watched the show Bones, you may be familiar with Zack’s colony of “flesh-eating” beetles kept for this purpose. (Zack: You can’t kill them. They have names.)

The scaled exoskeleton of a varied carpet beetle (Anthrenus verbasci).

These particular guys were varied carpet beetles, a fairly common indoor pest. Examining them under a scope reveals that these tiny, nondescript little blobs are quite striking. The beetles are covered with tiny, multi-colored scales in orange and white and black and their rotund little bodies, with legs retracting into grooves, mak them look something like carnival balloons. Pretty adorable for something that can leave a trail of carnage and destruction in its wake.

The legs of the carpet beetle can tuck back into grooves.

Luckily, the damage was fairly limited (the two specimens pictured here were by far the worst off) so I can consider the whole incident with amusement and interest. The pictures were fun. The collection? Is cycling through the freezer. Only dead bugs welcome in these boxes.

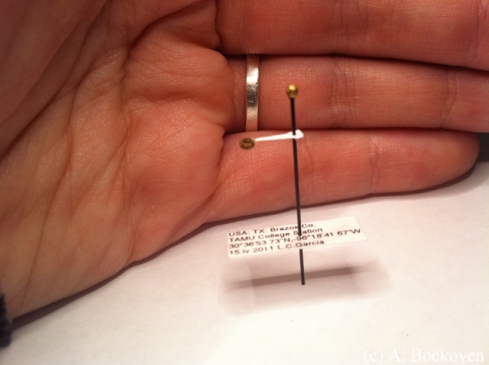

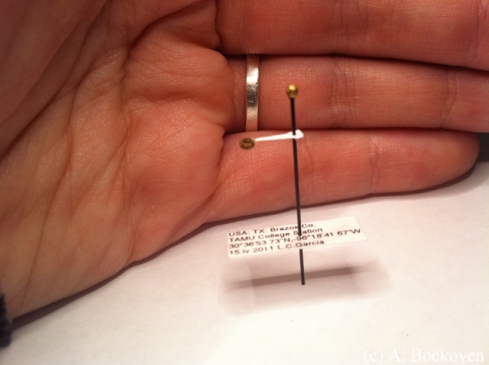

Pointed carpet beetle with hand for scale. (Thanks to Loriann Garcia for providing the pointed specimen for the impromptu photo shoot.)

—

A/N:

Can we talk for a minute about the fact that I took all these pictures with my cell phone? Forget hoverboards; we are living in the future. Right now.

It would never have occurred to me to point an iPhone down a dissecting scope without Alex Wild’s recent post over at Myrmecos. Clearly, I had tons of fun with this. I highly recommend it.

Tags: Anthrenus verbasci, Bee flies, Beetles, Carpet beetles, Flies, Insects, larvae, Moths, Tiger Moths, Varied carpet beetle

Recent Comments