Ants, like butterflies, are holometabolous and go through complete metamorphosis with an egg, a larva (~caterpillar), a pupa (~chrysalis/cocoon), and adult ant (~butterfly). In ants, the larvae resemble small white grubs and cannot move by themselves–they are fed and tended by the worker ants.

The larvae are covered in fine hairs which help them stick together in clumps, making it easier for adult workers to move and tend them. In fire ants, these hairs also help with rafting behavior, because they can trap a layer of oxygen around the larvae, helping them breathe and making them extra buoyant. Rafting fire ant colonies use their babies as tiny floatation devices. Please take a moment to consider the wonder of nature.

As they grow, the larvae molt several times, and each growth stage is referred to as an instar. The larvae pictured above are extremely tiny because they are first instar larvae, having only recently hatched.

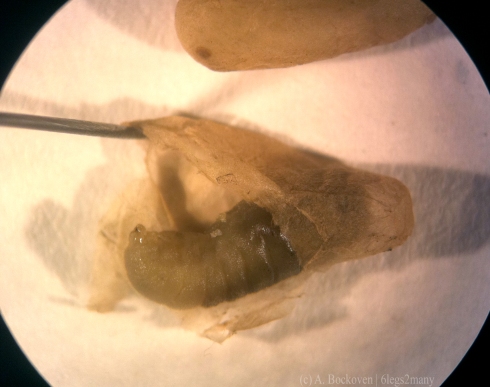

When the larvae are old enough they prepare to metamorphose into adults. Some ants, like these carpenter ants, spin themselves into cocoons to pupate, while others, like fire ants, leave their pupae exposed. Above, you can see an opened cocoon that contains a larvae that has not yet molted into its pupal form.

Additional fun fact: ant larvae have a closed digestive tract (I assume to prevent them from making a mess all over the colony. It’s like the ant equivalent of diapers.). They poop for the first time when they molt into pupae. Best line from a paper ever: “…the larva defecates for the first time…. Workers help out.” (Taber, 2000). This is also the least appealing job description.

While the job of the larva is eating and growing, the job of the pupa is developing–reorganizing its system into an adult ant. Ant pupa look basically like unmoving, pale adult ants, darkening up right before their final molt to adulthood. The newly molted ants are still fairly pale and soft-bodied. They are referred to as “callows.” Their exoskeleton darkens as it hardens, until they are prepared to go about the daily business of an adult worker ant.

PS: Here is a cool video of a queen ant helping a pupa shed its old larval skin.

Recent Comments